By Gene Roman

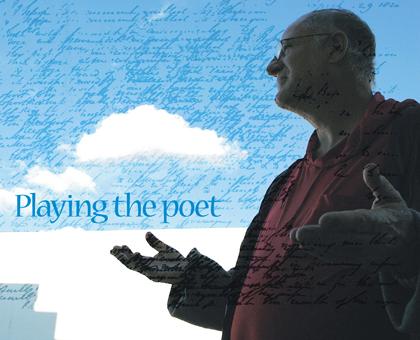

Allan Goldschmidt rises from his seat to read one of his poems. He then pulls a silver-plated flute out of a black case and plays “Lullaby of Birdland” by Duke Ellington to conclude his performance as a member of the Brownstone Poets.

Goldschmidt, 63, who has lived in Long Island City for 29 years, belongs to this citywide group of poets who meet twice a month at various locations throughout the city to share their work. He has been active with the group since 2004.

“I was very friendly with Evie Ivy, a belly dancer, poet and graphic artist from Brooklyn,” he said during an interview near Astor Place, where he works as a payroll accounting clerk for New York University. “It was through Ivy that I got involved with the Brownstone Poets.”

Goldschmidt said he discovered his voice as a poet through reading at open mic nights in Manhattan during the 1970s. He participated in a reading series started by Ivy called the “Moroccan Star Reading Series,” named after the restaurant that hosted the readings.

“I liked the camaraderie and the people who came to that reading series,” Goldschmidt said.

He then joined a group established by a girlfriend called the Scribblers in 1974.

Susie Kaufman, 58, who co-founded the group with Richard Spiegel, recalled their early days in a phone interview.

“My friend Richard lived next door and in 1973 asked me, 'Do you want to start a writing group?” Kaufman, a poet and songwriter, answered: “Sure, why not.”

Goldschmidt said he was invited to join the Scribblers after reading some of his poems at the Church of St. Paul and St. Andrew on the Upper West Side of Manhattan.

“I came to the Scribblers through an open mic night at the church in 1974,” he said. “A woman named Janet Bloom used to read these long poems and didn't respect the time limit,” he recalled. “The place was just there to give us a voice anyway.”

Goldschmidt remained active with both the reading series and the Scribblers through 1976.

He uses a style of poetry called villanelle to write much of his work.

A villanelle is a 19-line poem consisting of a very specific rhyming scheme. The first and the third lines in the first stanza are repeated in alternating order throughout the poem and appear together in the last two lines, according to Poets.org, the Web site of the Academy of American Poets. An excellent example of the form is Dylan Thomas's “Do not go gentle into that good night,” according to Poets.org.

“This is a style I really like,” Goldschmidt said.

But Goldschmidt was a musician first before expanding his talents into poetry.

“My father played the mouth harmonica,” he said. “I mimicked my father at first, even though I didn't consider the harmonica a musical instrument. But then the harmonica started hurting my lips.

“I had trouble singing, so I started playing the flute. Sometimes when I am playing, I feel like I can do anything and have music going through me a mile a minute. People have told me they would rather hear me play the flute,” he added.

He credits his father with inspiring his love of music.

“I grew up with a good ear for music due to my dad,” he said. “I have a special flute talent because I get into it so easily. I'm an ear person.”

He began playing his flute at poetry readings throughout the city before writing and reading his own work.

“I started playing background music as poets did their readings,” he recalled.

He spent five years in formal flute studies with Dan Soergel. Soergel works as an industrial designer by day and performs and teaches the flute in his spare time.

“He was my best friend Bruce Segerman's teacher as well,” Goldschmidt said.

It was Soergel who introduced Segerman to the shakuhachi flute, a traditional Japanese bamboo flute with five holes and a beveled blowing edge, according to Soergel's web site.

“I started Allan on the shakuhachi in 1998,” said Segerman, 60, of Levittown, L.I.

Segerman said he began encountering Goldschmidt at poetry readings in Manhattan 20 years ago.

“Allan and I have so much in common,” he said during a phone interview. “We both play musical instruments and we're both renaissance types.

“You know you're best friends with someone when you go to parties together and you're focused on the conversation happening between the both of you instead of the girls at the party,” he added.

Goldschmidt traces his interest in poetry to grammar school.

” I couldn't keep up with class lectures or note-taking, so I would start writing other stuff,” he said. “I had trouble getting along with my peers in school. They would call me grotesque and bizarre names.”

“I was thin as a child and teenager,” he said. “It was the girls at my summer camp that started calling me a 'tall, bald tickler.' I was not a typical kid and I think my naivete brought on some aggressive bullying from some of my fellow campers and classmates in school.”

He discovered during this time that he liked putting words together.

“But it wasn't until I joined the Scribblers in 1974 that I started feeling like a poet,” he said.

“I used to write 15 poems a month,” he said proudly. “There were times when I couldn't skip a day. I was also longing to connect with people and maybe even get a date.”

Goldschmidt grew up on West 102nd Street between Broadway and Riverside Drive.

“It was mostly Jews who had escaped the Holocaust then,” he remembered.

His parents, Fred and Anne, escaped to England in 1939. “My mother had to leave her family behind to die,” he said.

Goldschmidt's mother arranged for the release of his father Fred from the Dachau concentration camp through a letter-writing campaign to the German authorities, according to stories Goldschmidt recalled hearing as a child growing up.

Goldschmidt graduated from George Washington High School in Washington Heights in the spring of 1962. He began studies at Bronx Community College that fall. “I was on my way to finishing my A.A.S. degree when I transferred to City College,” he said.

After graduating in 1967, he went to work for Gimbel's. “I started out in sporting goods, but got pushed into yard goods,” he said.

In 1967, he walked upstairs to the executive offices to inquire about the executive training program. “Next thing you know, I'm working in the advertising/budget department,” he said.

After almost 20 years, Goldschmidt ended his career at Gimbel's in 1986, when the department store closed down. “It was a shock to leave the place, but I'm glad I did.”

Goldschmidt plans to retire from NYU in 2009 on the same day he started: July 12, 1993. He said he wants to dedicate himself full time to his poetry and music.

“I see myself as an exceptional individual, so I want to spend the rest of my life writing poetry and playing the flute,” he said.