By Erin Walsh

There’s a well-known saying that patience is a virtue seldom found in a woman, and never found in a man.

Photographer Robert Bergman is the exception that proves the rule.

At the age of 65, the photographer specializing in street scenes of everyday people is making his gallery debut at P.S.1 Contemporary Art Center in Long Island City, Chelsea’s Yossi Milo Gallery, and the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., which represents the latter museum’s first debut show. Twenty-four large-scale portraits of the artist’s street scenes, taken between 1985 and 1997, will be on view at P.S.1 through Jan. 4.

Prior to the current attention that Bergman’s work has garnered, his first informal exhibition was held in 1964 at a tiny bookstore called Savran’s near the University of Minnesota campus, where Bergman was a student before dropping out with his best friend Danny Seymour, who later moved to New York and befriended the eminent photographer Robert Frank.

“We would both take shots, and it was like a Bergman/Seymour, rather than a Seymour or Bergman,” he said of their early photo collaborations. “We knew Savran, and asked him to put his photos on his walls. There was no signage, no labels on the walls. My own argument would be that my debut was at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.”

There were lean years for Bergman between 1968 and 1976, when his mother would send him $200 “here and there” to help him survive.

“In 1972, I was really broke,” he said. “Didn’t have a shower that worked, had to go to a rich lawyer’s house to shower %u2026 Those were the days of 15-cent coffee, and you could sit there all day. A lot of my work was lost due to transient lifestyle from between 1968 and 1976.”

Bergman’s portraits that are currently on display at P.S.1 were taken between 1985 and 1997, during which time he would hop into his old gray Volvo station wagon and spend a month or two shooting in various American cities.

“How I got into color in Minneapolis was walking the streets,” he said. “At the same time, I wanted to figure out what a portrait meant to me. In the shooting season, when the days are longer, in the spring and summer, I would spend a month or two shooting. I went everywhere east of the Mississippi — the main cities: Minneapolis, Manhattan, Chicago, Youngstown, Pittsburgh, Boston, Cincinnati. The main places were Chicago and New York. Just everywhere. Just hop in the car in the morning with no plans. I’d say, ‘Well, let’s take a left here.’”

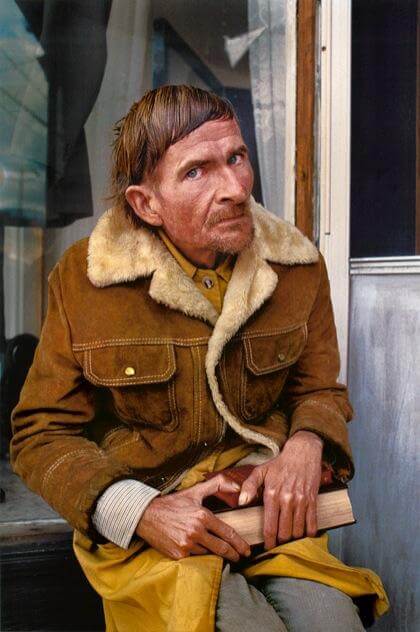

Bergman’s photos, which capture slices of everyday life ranging from a young girl giggling on the stoop of a home and an old women walking with her coat blowing behind her, her face showing signs of worry, to a young man wearing an argyle sweater underneath a coat with a faux-fur collar, his hair disheveled and his eyes sad and haunted, stubble gracing his chin.

“I would look for someone who interested me, and get out of the car and ask to take their photo,” Bergman said in reference to his subjects. “It’s too hard to define. It’s more intuitive. (I’m) certainly interested in individuality and what defines a person. I always trust my intuition. The intuition goes beyond the person — the attire, the way that the light falls, form and color. All of that in simultaneous conjunction with, ‘Who is this other person in America that I want to meet?’”

Bergman has been coming to New York since 1993, and now divides his time between Manhattan and Minnesota.

“New York is the only place that I love,” he said. “I have coincidences here that are magical.”

What’s next for Bergman? He is currently at work on archiving his work in Minnesota, but long term, his hope is that his art has staying power that extends beyond the current media blitz.

“One of the key questions is whether we can move this to the next level of discourse,” he said. “It would entail a curatorial interest from institutions and thoughtful essays that move away from me and all the fancy events. Right now, it’s more of a phenomenon. %u2026 I would like more discussion of the work, rather than [it] being about me. My hope is for the next generation to look at it, the way that someone might want to listen to a Dylan song again.”