By Jeremy Walsh

The 10-story building in Greenwich Village where 146 garment workers died in a fire that changed the political landscape of the state and the nation still stands.

But as its centennial approaches, much of the responsibility for remembering the tragedy has shifted to Queens.

Former Glendale state Sen. Serphin Maltese, whose family lost three members in the massive blaze, helps keep the memory alive with the Triangle Fire Memorial Association. The group will mark the 99th anniversary of the blaze at 7 p.m. March 25 at Christ the King High School.

“Since we put it on the Facebook page, we’ve heard from two more victims’ relatives that told us they aren’t on any list,” Maltese said of the social networking Web site.

The borough is also home to the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Memorial, a scholarship fund based in Long Island City, and a monument in Maspeth’s Mt. Zion Cemetery commemorating the dead.

The blaze started around 4:40 p.m. on March 25, 1911, probably when an employee threw a lit cigarette into a wastebasket. With six tons of scrap cloth lying around near tissue paper patterns and 40-gallon drums of lubricating oil stacked in the stairwell, the factory was soon ablaze.

The workers’ escape was also hindered by doors padlocked by the owners who feared theft and unionizing. As the fire climbed to the ninth floor, the workers, nearly all immigrants and many younger than 20, began to jump in groups, plummeting through the tarps held by firefighters on the ground.

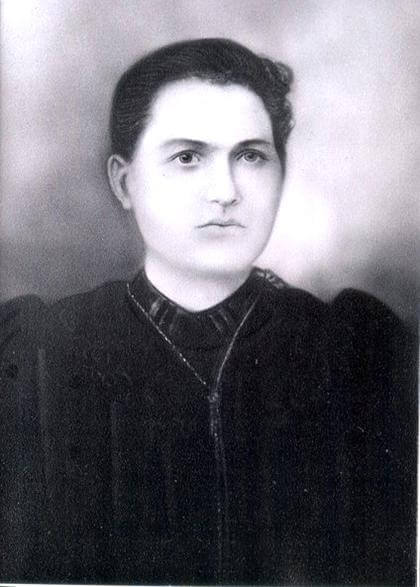

Maltese’s 38-year-old grandmother, Caterina, and her two teenage daughters, Lucia and Rosarea, were among the dead. They were buried in Calvary Cemetery in Maspeth, as were more than 40 other victims, Maltese said.

More than 1 million people turned out for the symbolic funeral for the 146 who died, and the reaction — along with the acquittals of the business owners on negligence charges — sparked a progressive movement in state government that led to the rewriting of many of the state’s building and worker safety laws.

Many of those at the forefront of the cause, including settlement house worker Frances Perkins, went on to play key roles in former President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal organization.

Roosevelt, who was a New York assemblyman when the reforms were being proposed, voted staunchly against each of them out of opposition to the Tammany Hall political machine that helped set the agenda, said Richard Greenwald, dean of graduate studies at New Jersey’s Drew University.

Greenwald, who wrote his doctoral thesis on the political ramifications of the tragedy, also hailed Maltese’s Senate record of opposing sweatshop practices during a lecture at the Queens Historical Society in Flushing Sunday.

Next year’s centennial will bring a pair of television projects to be aired on HBO, he said, noting he was pleased that the fire will return to the popular consciousness now that unions are on the decline.

“There’s fear that people … don’t know why it’s important, and it seems to repeat, this history of worker fires and industrial accidents,” he said. “Maybe it’s in Nepal or someplace else, but you’re seeing these patterns.”

Reach reporter Jeremy Walsh by e-mail at jewalsh@cnglocal.com or by phone at 718-260-4564.