By Joe Anuta

Oh, the irony. Western countries currently lead the Middle East in scientific innovation, but just over a thousand years ago, the situation was exactly the opposite.

A new exhibit, “1001 Inventions,” made its American debut at the New York Hall of Science Saturday and it seeks to dispel a widely circulated rumor about the years from the seventh to the 17th centuries.

These lost years are called the “Dark Ages” in Western textbooks, but Juniad Bhatti, a spokesman for the exhibit, said they were the golden years in the Muslim world.

“This is a subject that is not particularly well-known in this era,” he said. “It’s something that needs to be rediscovered because it has a huge impact on how we live our lives today.”

In fact, many visitors are shocked at the extent that Muslim culture has influenced western science, technology and even language.

For example, the word “sofa” comes from the Arabic word “suffah” and “traffic” from “taraffaqa.”

But the advances in science and mathematics drastically changed the world. Muslims invented the concept of zero, and we would not have modern math without it.

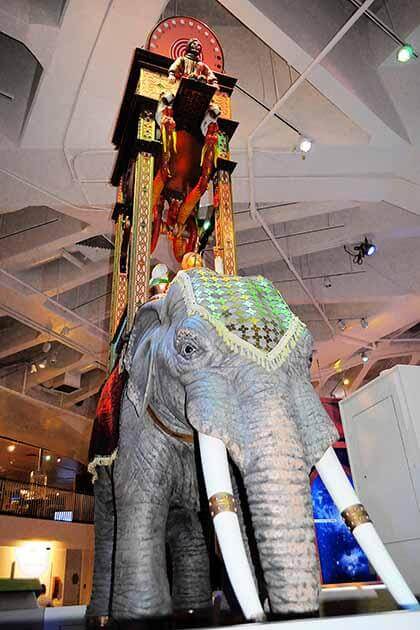

And Al-Jazari, an inventor who lived in the 12th and 13th centuries, created a system for converting circular motion to linear motion that has been used in machines for hundreds of years. An example of Al-Jazari’s work, a rod and camshaft, sits under the hood of almost every car in the world.

The exhibit consists of several eight-sided kiosks that are organized by subject matter like medicine, currency and astronomy. On each side, an illuminated plaque describes a specific piece of history and is often accompanied by interactive displays.

“We’ve tried to make it interactive as possible with touch screens and different ways of experiencing the exhibits,” Bhatti said. “We built this with the YouTube generation in mind.”

One theme throughout the exhibit seemed to be that the Muslim world feels slighted by Western textbooks.

One illuminated plaque read “credit isn’t always given where it’s due. For centuries, English medic William Harvey took the prize as the first person to work out how our blood circulates ….” But in reality, it was Ibn al-Nafis, although his journals were not discovered until 1924.

Ibn al-Haytham pioneered the scientific method of experimentation that is still taught in schools, and in the eighth century Al-Jahiz first developed theories of evolution and natural selection — 1,000 years before Charles Darwin was born.

The list goes on, but to dismiss the exhibit as setting the record straight would be doing it a great injustice, according to Bhatti.

“It was possible for people of different backgrounds to work towards a common goal and improve the lives of others,” he said, saying the exhibit is also about a shared knowledge that scientists from every background contributed to.

For example, scholars of every faith gathered at mosques and other centers of learning to exchange knowledge and translate books, and this spirit of inter-cultural harmony is one of the reasons Bhatti and other curators decided to hold the premiere in Queens, the most ethnically county in the United States and perhaps the world.

In addition, Bhatti said that the exhibit can help find some common ground in America, where Muslim and Christian interests have had some high-profile clashes.

“This is a valuable new way of demonstrating how much commonality there is between people of different backgrounds and diverse beliefs,” he said.

Reach reporter Joe Anuta by e-mail at januta@cnglocal.com or by phone at 718-260-4566.