By Tammy Scileppi

St. Albans artist Emmett Wigglesworth’s prolific career has spanned more than a half century, while his artwork has enhanced New York City’s cultural landscape since 1958, the year he moved here from his native Philadephia.

At 77, the muralist, painter and poet still draws on his cultural heritage and life experience when painting, and admits to scribbling fervently between projects. He believes in the creative metaphysical power channeled through his random pen and ink drawings.

“Initially, the scribbles took no form, but in time, I began to understand their direction and spiritual meaning,” Wigglesworth said in a recent interview. “Now, my scribbles represent the need for cultural understanding, for humankind to demonstrate their true capabilities — for love, acceptance and the Golden Rule.”

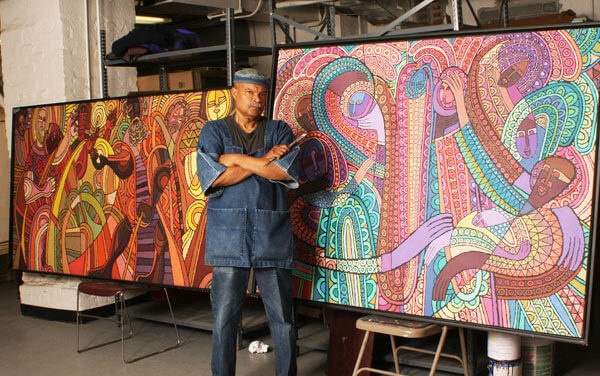

Working in his Brooklyn studio, the black artist is currently completing a series of 11 murals for the Addiction Research and Treatment Corporation and Urban Resource Institute in Brooklyn. “Once I finalize those I can begin working on my upcoming shows, which will be in Connecticut and New York,” he said.

Interwoven throughout Wigglesworth’s abstract murals and paintings are recurring themes: Motifs symbolic of African culture, featuring interconnected images of people: figures who seem to embody spirituality, humanity, beauty and power. Each piece is done in a range of hues within a specific color palette, using acrylic and colored inks.

Wigglesworth sees himself primarily as a muralist: “This medium allows people to get the message just by looking at the piece — at no cost.”

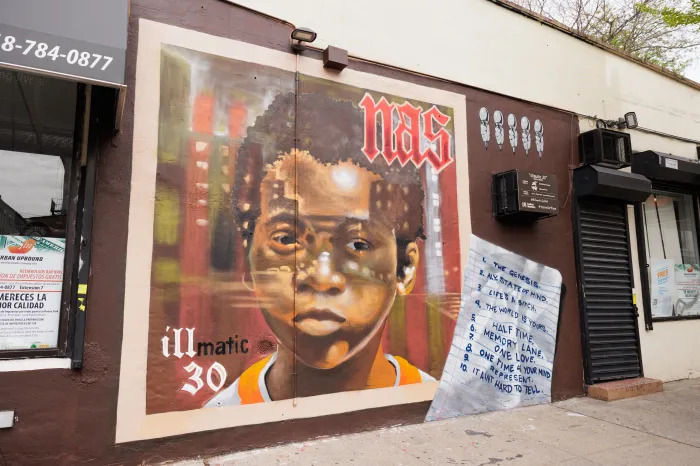

Listed on the roster of the MTA’s Arts for Transit program, which links neighborhoods to subway artwork, Wigglesworth’s murals grace many recognizable public spaces throughout the city — enlivening the Union Street, Brooklyn subway stop — where rushed commuters can glimpse the artist’s black and white silkscreen on porcelain enamel, adorning platform walls. Painted across a series of 22 panels set into recessed areas above subway station signs, Wigglesworth’s 1994 work “CommUnion” depicts intertwining figures comingled with serpent-like shapes and a brightly colored tile design..

“Representing the unification of different cultures in that area, the community above the Union Street station is mirrored in these panels,” Wigglesworth said.

And on a smaller scale, the artist’s acrylic on wood, jewel-toned mural and artificially illuminated stained-glass skylight provide a cheerful glow to a dimly lit auditorium in a Brooklyn’s PS 181.

In the ’50s and ’60s, Wigglesworth joined the civil rights movement and taught art at a CORE Freedom School, an alternative public school for young black students, in Selma, Ala.

He also hitchhiked across 38 states. Looking back, he feels all these experiences helped to shape the direction of his work: “Traveling all over the country as a black person during that period of time was an experience that could only be defined in my artwork, notes or poetry.

“Before this time, my work was more generalized on events around the world; afterward, I started focusing on events surrounding African-Americans in this country.”

“Once you realize there’s a positive message to your art, you have a purpose: understanding that the artist isn’t as important as the messages, which point out iniquities, and the need to search for spiritual truth,” said Wigglesworth.

The events of 9/11 made his desire to get out positive messages even more urgent: “After 9/11, I did a whole series of pieces depicting the need for patience and reasoning.”

In 2010, the Brooklyn Arts Council did a retrospective, honoring black artists of Brooklyn’s past, in which Otto Neals and Wigglesworth were featured. Neal’s work depicted the strength, beauty and spirituality of black men and women. “I met Neals in the ’60s, during the Black Arts Movement.”

In 1968, Wigglesworth designed the interior and exterior of the Bedford Stuyvesant Theater in Brooklyn, as well as costumes and stage sets for the Black Spectrum Theatre in Jamaica.

His wife, Sheilah, shares her husband’s artistic passion but her style differs dramatically from his, with realistic depictions of neighborhood life.

Last year, their artwork, along with the art of four other couples, including Hollis artists Rod and Jennifer Ivey, was on display in the “Partners in Art” exhibition, at the African-American Museum of Nassau County in Hempstead, L.I. Rod’s paintings depict buildings in early 20th century Ohio, Illinois and New York.

Rod Ivey, who has been a part-time page designer for TimesLedger Newspapers for more than 12 years, is Wigglesworth’s colleague.

Wigglesworth’s work has been exhibited throughout New York City and the country. He has designed and illustrated several books and magazines for Harper & Row, McGraw Hill, Macmillan Press, and Sesame Street.

“It seems that in a time of materialism, self-interest, and self-gratification to the extreme, the purpose of life has been forgotten; so, too, has the purpose of talent,” Wigglesworth said. “The enhancement of humanity gives life and talent meaning. It’s my hope and prayer that by using my talent in a functional way, I can remind humanity of the need to search for, and put into practice, spiritual truth.”